The Hundred - Analysing the Powerplay

Jack Hope takes a look at how teams in The Hundred are approaching the powerplay versus in other T20 competitions

With a handful of matches played one of the most common refrains about The Hundred has been that it is very similar to T20 cricket. With only 20 balls an innings difference between the two forms of the game that is an obvious conclusion to draw. However, in a few key areas there are differences.

One of the most significant of those differences is the powerplay, which is both shorter in terms of number of balls, and also in terms of the proportion of the innings.

Seven matches into the tournament it is hard to draw firm conclusions about the impact this is having on the game, but based on the data presented in the table below, it appears that there are some themes already developing when The Hundred is compared to England’s other domestic T20 tournament, the Blast, and the most well regarded franchise league, the IPL.

In short, so far in The Hundred, teams are taking more risk in the powerplay versus other short form comps. The consequence of this has been a small increase in runs scored per ball, compared with the other two tournaments, in exchange for a major increase in the frequency of wickets falling.

What might this mean?

Based on the above there are a few assumptions we can make, or hypotheses, worth testing, about the powerplay in The Hundred. For example:

It’s fair to assume the powerplay is a less important batting phase in The Hundred than in T20 competitions. Whilst the fielding restrictions still make it the easiest phase of the game to bat, the Hundred’s format appears to reduce the impact of the powerplay on the game in two ways.

Firstly, there is the simple fact that it only makes up 25% of the innings, rather than the 30% seen in T20. Secondly, the 11 balls lost in The Hundred’s powerplays are the 11 juiciest deliveries sent down in the T20 equivalent. In a T20, at this point in the innings, the ball has stopped swinging and at least one of the two batters has established themselves at the crease. Usually this spells bad news for the bowlers.

It changes what we should look for in top order batters. Successful short form batters rely on their ability to maintain a high boundary percentage. Top order batters have an advantage in this part of the game, as they bat during a period when the fielding team are unable to cover large parts of the boundary. At present a significant portion of the successful top order T20 batters are successful because of their ability to exploit this and hit fours. Take this away from them and they are less valuable to a team than at present. It also increases the value of top order batters who are able to more frequently clear the ropes.

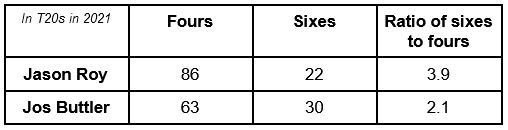

This dynamic is illustrated by the current England T20 opening pair: Jason Roy and Jos Buttler. Jason Roy has established himself as a good T20 opener (at least at the domestic level) by consistently piercing, or clearing the infield to hit fours. If fielders can patrol the ropes from earlier in the innings he loses one of his advantages sooner in the game.

Buttler on the other hand clears the ropes for 6 on a far more regular basis than Roy. Fundamentally, hitting the ball into the stands is obviously a good strategy to avoid boundary sweepers. Players with a good 6-to-4 ratio should be more important.

Bowling powerplay specialists matter less, at least from a bowling perspective. Despite wickets falling more regularly in the powerplay overs of The Hundred, scoring rates have not declined too drastically later in the innings, probably because there are fewer overall balls in the innings which negates the need to preserve batting resources.

Data also suggests that bowlers who bowl 10 balls in a row get hit harder in their second 5 than their first 5. This is a problem for the theory that using a single powerplay specialist to bowl the bulk of this phase of the game could be a profitable strategy.

Wickets in the powerplay probably matter less. There is a noted phenomenon in T20 cricket that if you lose 3+ wickets in the powerplay your chances of winning fall to lower than 25%. It is probably fair to speculate that this will not be the case in The Hundred, primarily because the condensed nature of the game reduces the value of wickets overall.

Indeed, whilst we are only 7 matches into the competition, on both occasions when a team has been 3 wickets down at the end of their powerplay they have gone on to win the match

Reflections for the IPL

There is a clear contrast in approach between the two England based competitions and the IPL. Teams across the IPL are significantly more circumspect during the powerplay, looking to cash in later by keeping wickets in hand. To some extent this works, as IPL teams buck the trend seen in the Blast and The Hundred and are able to score faster after the powerplay. Unfortunately the scoring rate they achieve in the later part of their innings still falls below the rates seen in the Blast and The Hundred.

It is worth noting that this trend is likely to be influenced by the conditions the competitions take place in, which do necessitate a different approach to the game. However, it is also safe to conclude that IPL teams are generally too cautious in the powerplay, and that broadly they are failing to make the most of the easiest period of the game to bat in.

And…

If all that powerplay number stuff is too boring, then fair enough, here’s Alex Hales giving it a whack!

Make sure you hit follow, and find us on Twitter @thecricketpod. And catch our latest episode below:

Do you think we will see shifts in the type of players teams aim to recruit next year based on this years hundred?