Dom Sibley For England - Batting Long is Good

Jack Hope takes a look at Dom Sibley and batting long. Did he learn an anything he didn't know already? No. But he spent too long on the graphs not to publish this.

Jack Hope takes a look at Dom Sibley and batting long. Did he learn an anything he didn't know already? No. But he spent too long on the graphs not to publish this.

Sibley stay or Sibley go?

In the wake of the drawn first Test match between England and India the English media have been on the warpath. Devastated to have achieved a positive result against one of the best two teams in the world, the press are out for blood. On this occasion, Dom Sibley is the man in the crosshairs, as in the last few days, Vaughan in the Telegraph, and Tim de Lisle of The Guardian, have bridged the political divide to demand that Sibley must go.

And to be fair during the Trent Bridge Test, in which Sibley scored 18 and 28, whilst using up 203 deliveries, it did appear that he was a slightly over-promoted nightwatchman. However, judging a man nicknamed “The Fridge” based purely on aesthetics is always going to be a biased exercise, so to try and do him justice and to drum up support for Ross Legg’s Dom Sibley fan club, here are some graphs.

Dom “The Fridge” Sibley - Cricket’s Hold Music

The obvious place to start here is a comparison of Dom Sibley with his peers, and on this level he fares reasonably well, in the middle of the pack of England openers with 10+ innings played since 2011. It is also worth noting that 6 of Sibley’s 21 Tests came in India and Sri Lanka, and the avant garde batting surfaces that came with it.

When compared more generally with the overall average of England openers in the last decade, his average of 30.32 falls below the overall mark of 34.63. However, that figure includes the runs scored by England’s freak god, Alastair Cook. England openers not named “Cook” have averaged 29.11, a figure that Sibley sneaks past.

Now, it must be said that a team with serious aspirations to reach number one in the world, or challenge for the World Test Championship, should obviously not be satisfied with Sibley’s bang average run production. However, that isn’t where this England team stands in the world. Their short term objective, beating India, and the medium term goal, not humiliating themselves down under, both require them to achieve results against better teams. This is where Dom Sibley comes into his own.

Simply put, batting time increases the chance of a draw. Draws are useful for the 2021 England side. No other candidate to open the batting bats as much time as Dom Sibley.

The first Test of this series provided an example of this value. If Dom Sibley had scored his runs at the same pace as Zak Crawley in that Test, he’d have faced around 100 fewer balls. Assuming India’s chase had started that much earlier, and they maintained the same run rate, they’d have finished day 4 within 100 runs of victory.

Obviously it would have rained irregardless, and the match was going to be drawn either way, but Sibley’s efforts made the draw the most likely result as soon as the first drops fell, effectively shortening the window of time India had to achieve a result.

The Cowan, The Dentury, The Sibtury?

It is highly unlikely that The Sibtury is going to catch on as a cricketing term (so I welcome alternative suggestions), but the idea that a top order batter facing 100 balls could benefit their team, beyond the runs they have scored, is not new. It isn’t really clear why 100 balls is the golden number, but as it is pretty simple to filter for those occasions, that is what we are using as a measure of whether an opening batter has sufficiently blunted the opposition’s attack.

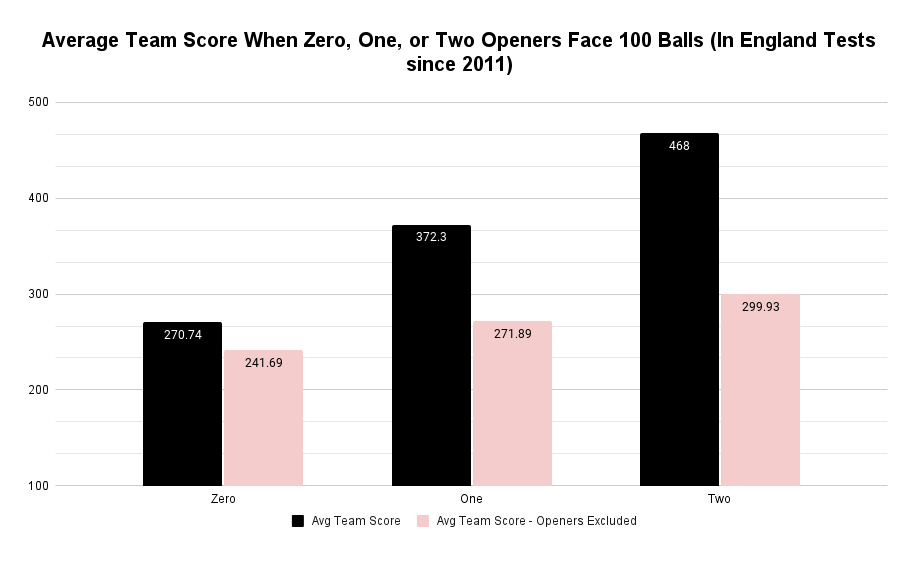

In any case, if it is true that this approach is beneficial, then as seen in the chart above, Sibley could be playing a vital role for this England side. And, at first glance, this does appear to be the case.

Now clearly this isn’t an open and shut case, other factors are going to influence these results (for instance the quality of the opposition, it is reasonable to assume that when Team A is better than Team B, they are more likely to see their openers face 100 balls and more likely to score heavily later in their innings), but there is an obvious trend.

Beyond this, it is possible to take a more comparative approach to assessing the value of an opener facing 100 balls, by looking at first innings scores when one team outperforms the other on this metric. Below you can see the average difference in runs achieved by teams when either one, or both, of their openers face 100 balls, but the other team’s don’t.

This demonstrates that in roughly similar conditions, across the first innings of Test matches, there is an advantage to having your openers reach 100 balls faced. Although it happens rarely (only 9 times in the last 128 England Tests) when a team outperforms the opposition 2-0 on this metric the difference in overall score is colossal. That much was to be expected, however when only 1 more opener reaches 100 balls than the opposition, the difference in average outcomes is still reasonable.

Sibley detractors could probably ask, at this point, whether his low strike rate would eat into this expected benefit, and they would probably have a point. There are certainly other factors at play here that would explain some of the difference in average outcomes, the relative ability of the competing sides, match conditions, the fact that the middle order will play differently based on the match situation set up by the openers, probably all enter into the equation.

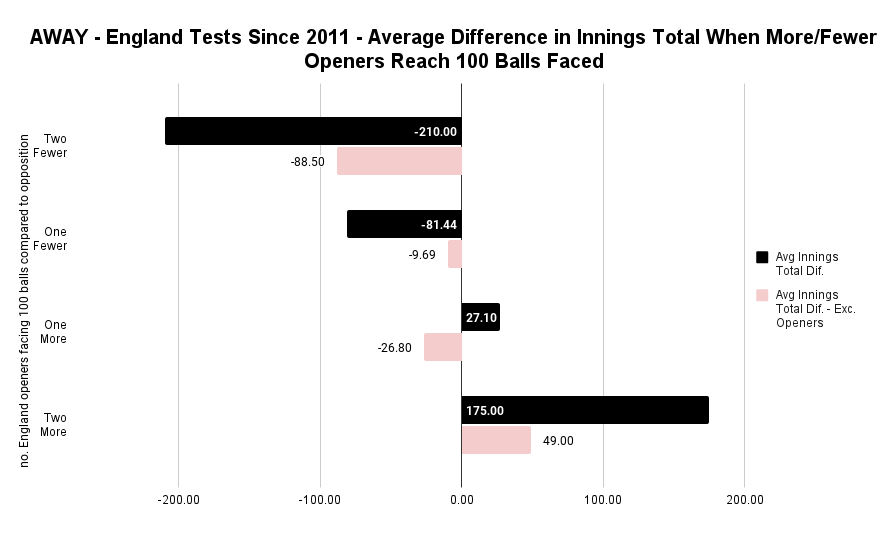

However the benefit is probably slightly understated by the chart above. Particularly at home, where the rhythm of the game dictates that an opener seeing off the new ball should offer more protection to the rest of the team than in, say, the sub-continent where spin is the primary threat. The charts below, splitting England Tests into “home” and “away” matches bear this out:

The charts also show a couple of other interesting points Firstly how different conditions impact the game. In both cases the home team is able to derive a far greater advantage from a position of strength, than when the away team finds themselves in a similar position. Secondly, the role of the traditional opener looks to be more useful in England than away from home.

Marcus Trescothick - The Fridge Repairman?

What does this all mean for Sibley? Well in the short term it is probably largely good news. His numbers to date are not necessarily bad versus what others have achieved. In England’s current circumstance he adds value by making them hard to beat. Broader data suggests that openers capable of batting time, take the shine of the ball, tire the opposition and make it easier for the rest of the team to score runs. Dropping him is likely to be a counterproductive move. Trying to improve him would be a better option.

And briefly it is worth considering the role of Marcus Trescothick in this, a new coach to the England set-up. Over his career Trescothick put up a solid average at a formidable strike rate, for an England opener. Surely, you would think there is a role for him to play here, to create a more proactive version of Sibley.

A full scale revolution is clearly out of the question, but if England could find a way to nudge Sibley’s strike rate up a few points, without compromising his ability to hang about, they may have an opener for the long term.