Analysing Spin Bowling In The Hundred

Jack Hope takes a look at the performance of spinners in the Hundred

In the lead up to The Hundred I made a prediction, on the podcast, that spinners would do less well in the competition versus their performance in regular T20 matches. Now that we are a few weeks on from the end of the tournament I thought it would be interesting to see whether that prediction turned out to be true.

This is a pretty esoteric topic and, again, I didn’t mean to write 1000 words on it. However I think working out how this game actually works is really fascinating, so things got out of control. If this is your bag, you can follow me on Twitter @JackHope0, and I’ll never miss a chance to plug our absolutely awesome podcast, which you can find here.

The hypothesis - Do you still spin to win?

It is generally observable, across global short form cricket, that spinners are more economical bowlers than seamers. This reality was reflected in the original draft, with Rashid Khan being taken with the first pick, before Narine, Tahir and Mujeeb all also went within the first two rounds. Mitchell Starc, meanwhile, was the only pace bowler taken in those rounds.

However, there was reason to believe that this may not hold true in The Hundred. A normal T20 can be divided into three phases: the powerplay, the middle overs, the death. I speculated that removing 20 balls from a T20 would have the most disproportionate impact on the relatively more sedate middle overs. Overs which are usually dominated by spin.

Therefore I expected spin bowlers to perform less well versus seam bowlers, in comparison to their performance in T20s.

What does the data tell us?

How did that hypothesis work out?

If you take one thing away from this article, it should be that spinners were more expensive than in T20s, but they were still more economical than seam bowlers.

A quick comparison of the most economical bowlers in this season’s T20 Blast and The Hundred immediately demonstrates that there was a shift. In the T20 Blast 4 of the top 25 most economical bowlers in the Blast bowled seam up (and one of those was Ravi Bopara!). In The Hundred, this number surged to 10 of 25.

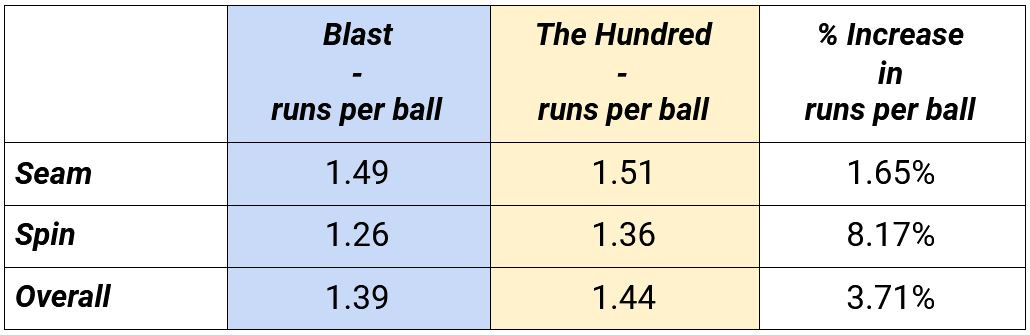

In a little more detail we can see that the increase in scoring in The Hundred, versus The Blast (we are using the Blast as a comparison as it is a tournament with an overlapping player pool and set of venues, which removes a few variables), was almost entirely down to batters scoring faster v spin bowling.

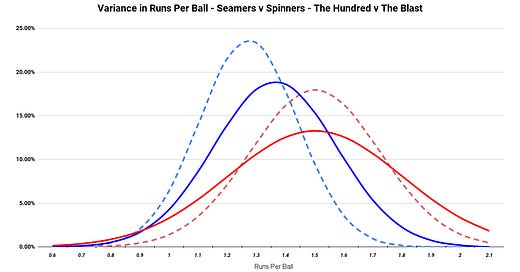

We can also see another interesting trend when we compare the normalised distribution of the two types of bowlers in both tournaments. This is shown in the bell curves below (blue for spin, red for seam, dashed for The Blast, un-dashed for The Hundred).

In both cases we see the curve flatten, which indicates that there is a bigger difference between the better, average, and worst bowlers in The Hundred than in The Blast. A phenomenon which is more noticeable for spinners.

We also see the curve for spinners shifting to the right, as their economy rates rise, reflecting the table above. When compared with seamers the two curves also illustrate how a far greater proportion of the seam bowlers in The Hundred are able to bowl with economy rates comparable to spinners, than in The Blast.

Why is this happening?

Firstly, the loss of 20 balls in the innings is probably playing a role. Batters already target the powerplay, as the fielding restrictions make scoring runs easier. They also target the death overs, as they want to use the last balls of the innings efficiently. This leaves the middle overs, where batting intent traditionally decreases.

This makes it an obvious phase to attack to improve overall scoring efficiency, which, as the main bowlers of this phase, would explain why spinners are overall more costly in The Hundred. An interesting piece of follow up research would be to compare scoring rates in the three phases between The Blast and The Hundred, to confirm this link.

Another reason that jumps out is that left arm off-spin was flat out whacked in The Hundred. Over the tournament those bowlers conceded 1.47 runs per over, versus just 1.24 in The Blast, an 18% increase. Whether this is happening because of poor selection, poor match ups, better batters, or another reason, is less obvious.

Finally, it is worth considering whether this is just noise. With a small amount of data for The Hundred format available it is possible that a handful of freakish performances, or matches played in unexpected conditions, could be affecting the data. Whilst the player pools and venues overlap between the two competitions, they are not identical, and we need to be aware of this.

With more runs, come more wickets…

So far we have only focussed on economy rates and not on the wicket taking capacity of the two types of bowler. In this area spinners, in The Hundred, performed exceptionally well. Collectively they improved their bowling average from a level worse than seam bowlers, to better.

This change is largely explained by a huge drop in the bowling average of leg spinners, dropping from by more than 5 runs, highlighting their attack threat. The other three types of spinner performed roughly as well as they had in The Blast on this metric.

This data could also back up the idea that batters in The Hundred are happier attacking spin than in a T20. Obviously bolder stroke making comes with an increased likelihood of a batter losing their wicket, which could be the case here.

I am also unsure how much importance should be given to this change. The value of wickets in T20 cricket is already lower than many appreciate, a situation only amplified by removing 20 more balls from an innings. It is definitely good for spinners that they are more threatening, but I don’t think it mitigates the rise in economy rates.

What we learn and are we seeing the future?

It may change draft strategy. Earlier in the piece I mentioned that, from a bowling perspective, the early rounds of the draft were dominated by spin. Based on the 2021 edition of the event, teams should consider whether that is still the most effective strategy. There is certainly less to choose between top end spinners and top end seamers, in terms of run prevention.

It reinforces the value of spin in short form cricket. Whilst the relative value of superstar spinners may have fallen, the value of spinners in general is still evident. Match-up opportunities provide teams with many options to “improve” a spinner that are not as available for seam bowlers. The fact that spinners also ended the competition with a lower combined bowling average than seamers is another feather in their cap.

This could be a window into the future of T20. As the T20 game changes it is possible that these numbers similar to the above may be replicated in other T20 competitions. At present you could take a view that teams are not scoring as highly as they should be during the middle overs in the T20 format. If this is the case then The Hundred has given us a small glimpse at what the future may hold for spin bowling in T20 cricket.

Conclusions

Linking back to the original hypothesis, I think we can say with reasonable confidence that there is a kernel of truth there. However, the fact that spinners are less economical relative to seamers, in The Hundred when compared with The Blast should not obscure their undoubted value.

Do I think the value of premium pace bowlers has risen as a result of the above? Absolutely, especially those who can bowl at the death, and they may well be my top target in constructing a team. Having said that, a good battery of spinners is still a sure root to success in this format. I’d be particularly interested in picking up right arm leg spinners, who took wickets for a lower cost, without a substantial impact on their economy rate.

… and housekeeping

I should also acknowledge the role of fellow podcaster Max Rowe-Brown in this article. His input on various graphs was invaluable.

I have one more article planned on the 2021 edition of The Hundred, which should be out sometime next week or so (so make sure you sign up to this substack!). We also have a podcast out pretty much daily at the moment as we navigate through towards the end of the England v India Test series, which you should also subscribe to!

Following on from that, and my last article, I want to take a deeper look at the value of rolling batting averages in Test cricket, and examine the link between First Class performance and Test performance in a couple of countries besides England.